Before zeroing in on any particular strategy or investment vehicle, retirees need to understand how much risk they are willing to tolerate in the context of their entire portfolio and the corresponding rate of return that can reasonably be achieved.

While each of us will ultimately reach different conclusions and asset allocations, we are united by common desires – to maintain a reasonable quality of life in retirement, sleep well at night, and not outlive our savings.

Most retirement paychecks are funded by a combination of investment income and withdrawals of principal. Retirement income generators such as annuities or systematic withdrawals often provide more upfront income than a dividend strategy.

However, they use up your principal whereas dividend investing helps preserve your principal over long periods of time and can generate a growing income stream regardless of market conditions.

It goes on to state that you invest $400,000 into Treasury bonds and $600,000 into stocks that yield 3%, good for $18,000 in dividend income each year. After spending every dollar of dividends, you sell part of your bond portfolio to hit your $40,000 inflation-adjusted annual income target. After about 21 years, your bond portfolio would be fully depleted.

However, over that time period, your annual dividend income might have grown by a third to reach $24,000 per year, even after accounting for inflation. Most importantly, you would still own all your stocks.

If your dividend income grew by about 33% after adjusting for inflation, then it is reasonable to believe that the value of your stocks could have appreciated by a similar amount as their growing cash flow made them worth more over time, perhaps reaching close to $800,000 in value.

Assuming you retired no sooner than the age of 60, you would now be in your 80s and have a healthy amount of funds left for the rest of your retirement.

As The Wall Street Journal’s example showed, building a growing stream of dividends can help offset today’s low bond yields while avoiding problems caused by potentially inflated stocks prices – high quality dividend stocks can continue raising their dividend during bear markets.

While some retirees on a systematic withdrawal plan would feel pressure to cut back during stock market declines, you can enjoy a pay raise with the right dividend stocks.

Let’s take a closer look at the benefits and risks of leaning on dividend income in retirement.

Living Off Dividends: The Benefits of Dividend-Paying Companies

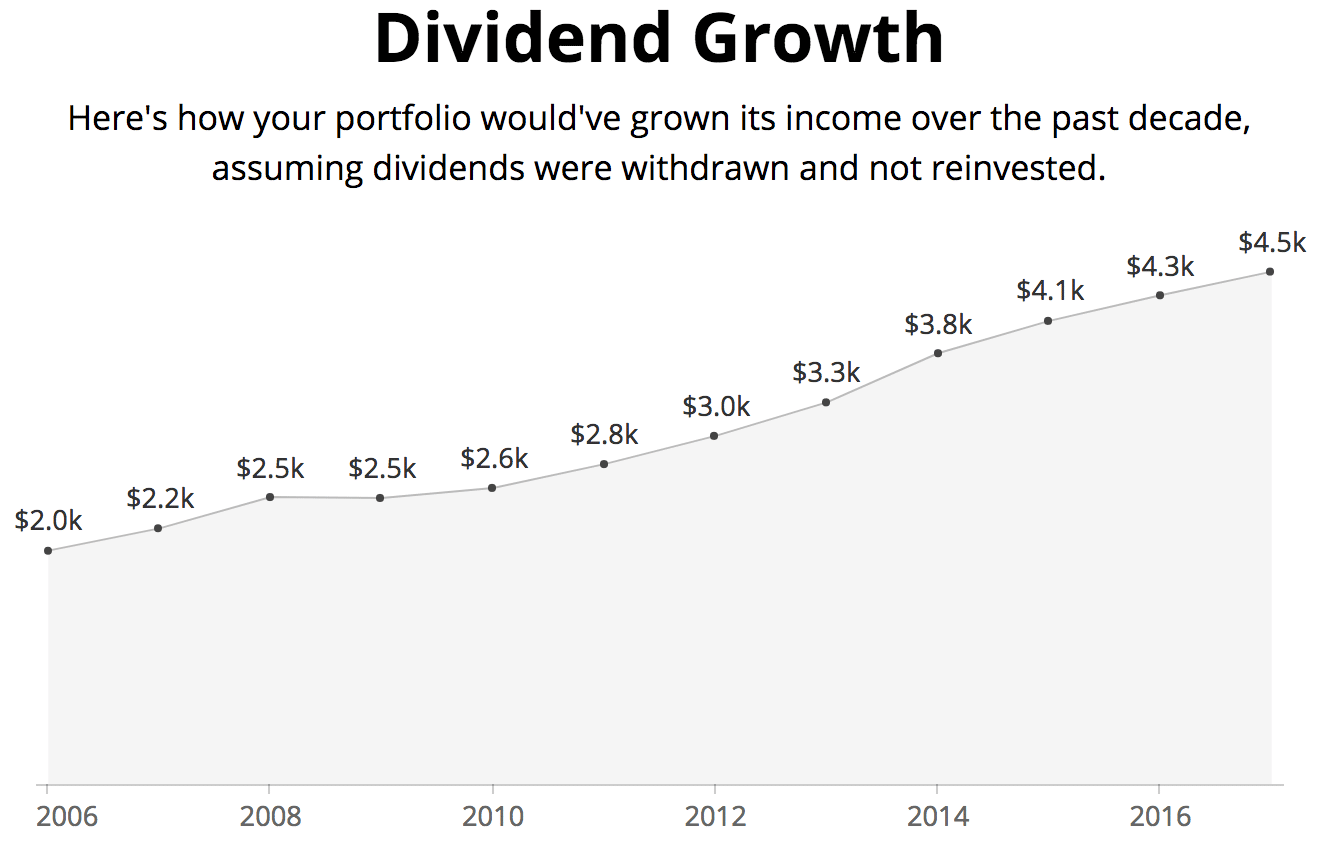

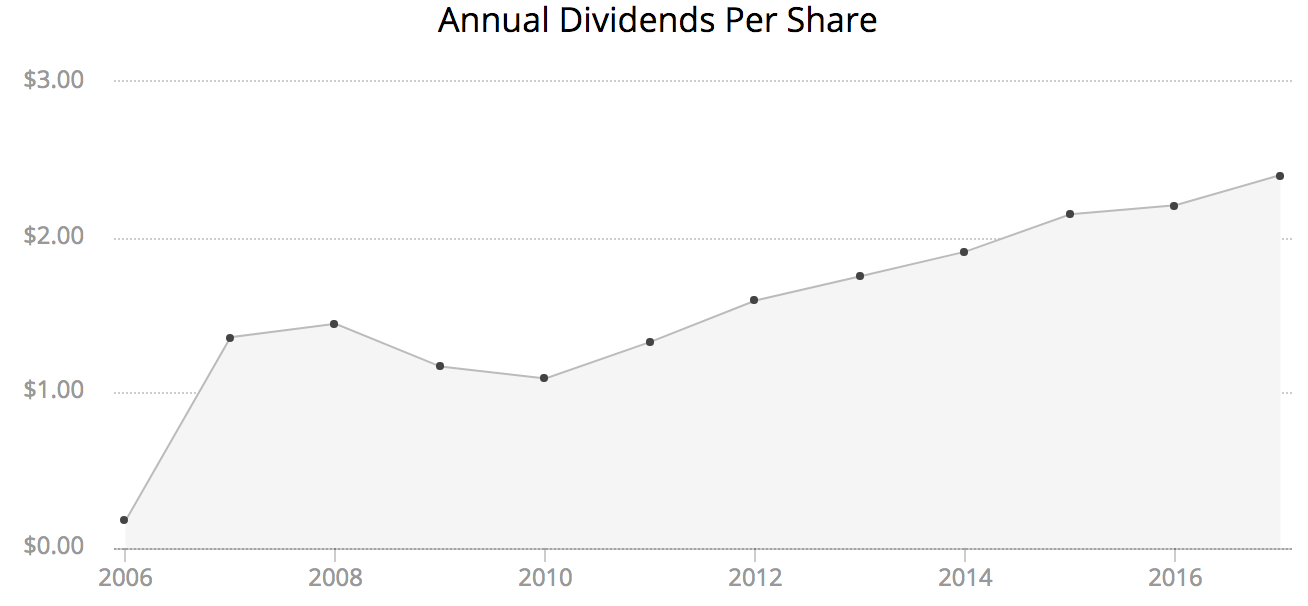

While a portfolio of dividend growth stocks will experience some variability in market value, the income that a good portfolio churns out should consistently grow over time. Even during the financial crisis, over 230 companies increased their dividend.

Living on dividend income in retirement provides cash without incurring the stress of figuring out which assets to sell and when, especially if another market crash is around the corner.

Once again, the focus can remain on locating safe dividend payments rather than getting concerned with the market’s price volatility and how that might impact your withdrawal amounts. As long as there is no reduction to the dividend, income keeps rolling in regardless of how the market is behaving.

A great example is our Conservative Retirees model dividend portfolio in our monthly newsletter. While the S&P 500 Index plunged more than 50% during the financial crisis, the stocks we hold would have delivered steady dividend income during this period.

Another benefit of owning dividend stocks in retirement is that many companies increase their dividends over time, helping offset the effects of inflation.

According to the Wall Street Journal, over the past 50 years the S&P 500’s dividends grew at an average 5.7% per year, outpacing the average 4.1% inflation rate. While past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results, retirees who depend on a meaningful amount of dividend income are likely to be in a good position to protect their purchasing power with the right dividend stocks.

Additionally, a dividend investing strategy preserves and grows your principal over long periods of time, unlike most annuities and withdrawal strategies. This allows you to leave a legacy for your family or favorite charities. Dividend investing also provides flexibility to sell off assets if you need to fund special retirement activities or offset some unexpected dividend cuts. Once again, annuities typically lack this flexibility.

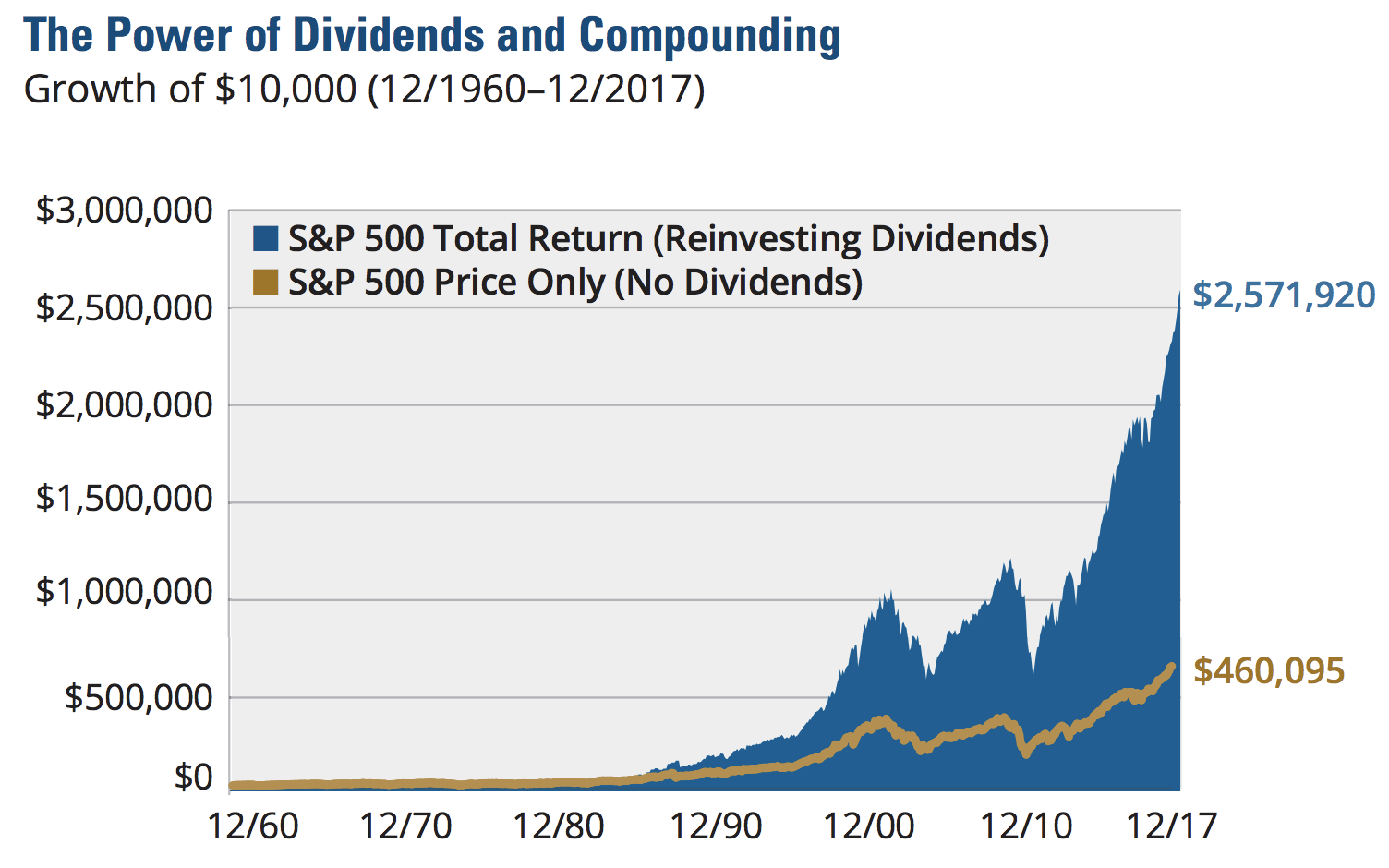

But what does that really mean? Well, suppose you made two $10,000 investments into the S&P 500 back in 1960. One investment received no dividends. Its value was completely driven by the rise (or fall) of the market.

The other $10,000 investment received dividends paid by the S&P 500 companies, reinvesting the payments back into the S&P 500 as they were received.

The latter investment grew to more than $2.5 million by the end of 2017 compared to less than $500,000 for the other investment. Dividends matter.

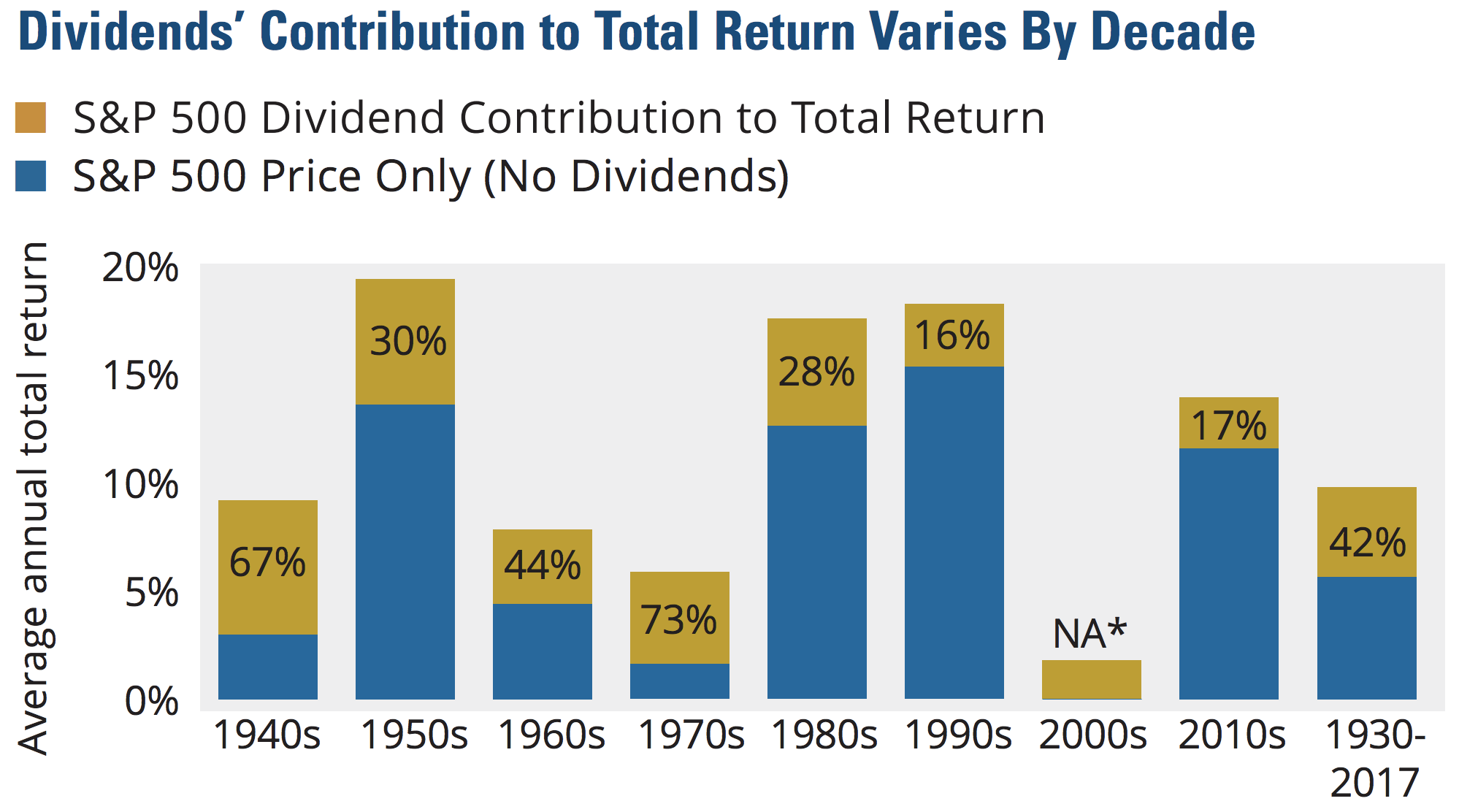

As you might have noticed in the bar chart above, the relative importance of dividends varied from one decade to the next depending on the strength of the market’s price performance. During periods when stock prices stagnate, such as the 1970s and 2000s, dividends make up a greater portion of the market’s return than capital appreciation.

With the market trading at a historically elevated earnings multiple today, making significant capital gains harder to come by, dividends seem likely to account for a meaningful proportion of the market’s total return over the next decade.

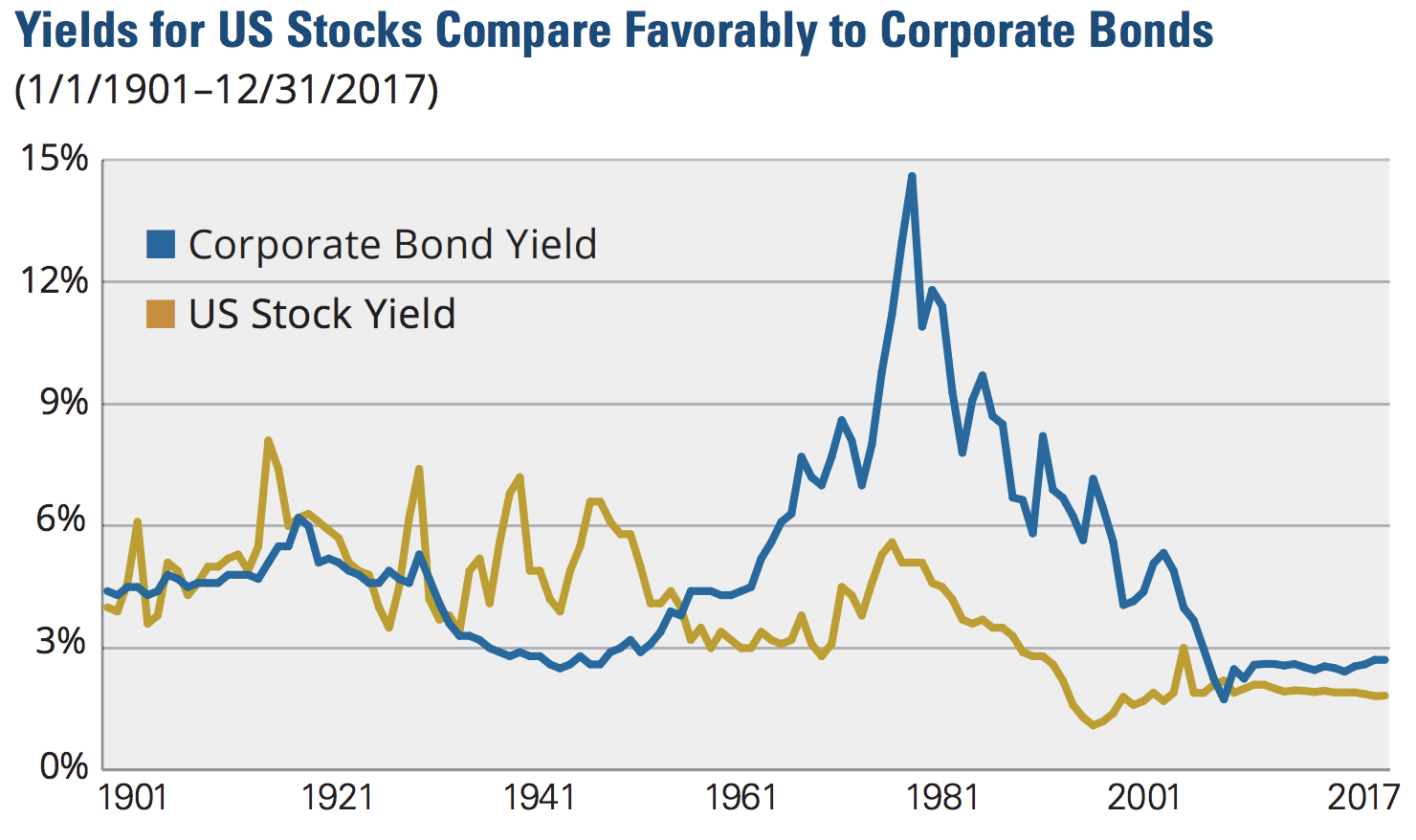

Either way you look at it, stocks are much more attractive than bonds in today’s market environment. The financial world has changed a lot over the last 40 years. As you can see, long gone are the days of double-digit bond yields. Many quality stocks now yield significantly more than corporate bonds.

As Warren Buffett stated in May 2018, “Long-term bonds are a terrible investment at current rates and anything close to current rates.”

Why the hate for long-term bonds? Like many things, it’s simple math for Buffett. Long-term bond yields are 3% today, and their interest income is taxable at the Federal level. In other words, their after-tax yield is about 2.5%.

Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve is targeting 2% annual inflation. So the long-term bonds’ after tax return, adjusted for inflation, is approximately 0.5% per year.

As Buffett put it, long-term bonds at these rates are “ridiculous.” It’s hard to disagree when you consider that long-term stock returns are close to 10% per year, and, unlike bonds (which make fixed interest payments), dividend stocks grow their payouts.

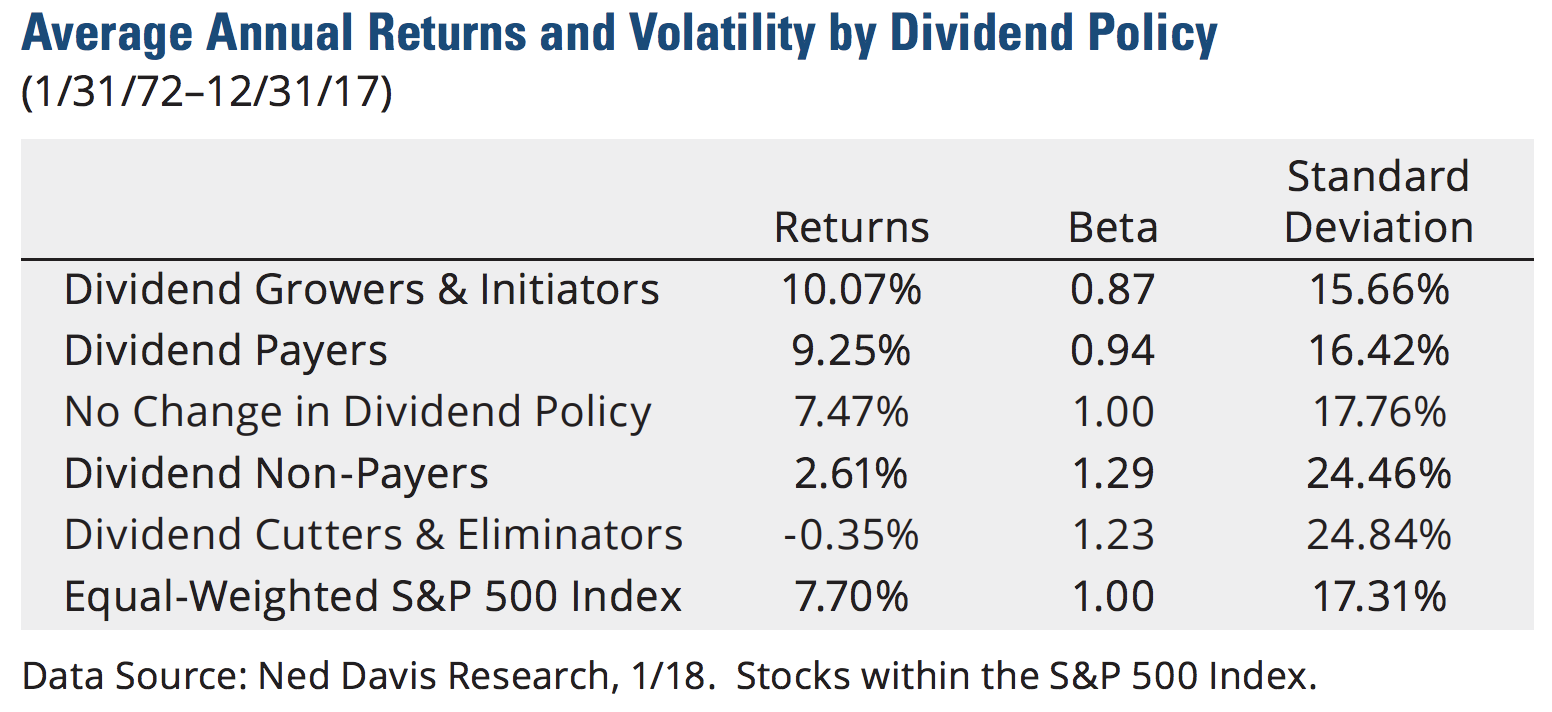

As seen below, dividend-paying stocks in the S&P 500 Index have recorded significantly less volatility (i.e. a lower standard deviation) than non-dividend paying stocks over the last 45 years.

In order to continuously pay a dividend, a company must generate profits above and beyond the operating needs of the business and tends to be more careful with their use of cash.

These qualities filter out many lower quality businesses that have too much debt, volatile earnings, and weak cash flow generation – characteristics that can lead to large capital losses and sizable swings in share prices.

The lower price volatility profile of dividend-paying stocks is attractive for retirees concerned with capital preservation.

Investing in individual securities yourself eliminates the costly fees assessed each year by many ETFs and mutual funds, saving thousands of dollars along the way. All you pay is a one-time commission cost (typically $10 or less per trade with discount brokers) to execute your initial trade to buy the stock.

Higher fees mean less dividend income for retirement. The relatively high fees charged by most fund managers are also a key reason why Warren Buffett advised the typical person to put their money in low-cost index funds for the best long-term results in his 2014 shareholder letter:

“My advice to the trustee couldn’t be more simple: Put 10% of the cash in short-term government bonds and 90% in a very low-cost S&P 500 index fund. (I suggest Vanguard’s.) I believe the trust’s long-term results from this policy will be superior to those attained by most investors — whether pension funds, institutions or individuals — who employ high-fee managers…

Both individuals and institutions will constantly be urged to be active by those who profit from giving advice or effecting transactions. The resulting frictional costs can be huge and, for investors in aggregate, devoid of benefit. So ignore the chatter, keep your costs minimal, and invest in stocks as you would in a farm.”

Suppose the $1 million was invested in a dividend-focused fund yielding 3.5%. Over 28% of the $35,000 of dividend income generated would go towards fees.

But what about some of the low-cost dividend ETFs with fees as low as 0.1%? In many cases, investors who are less willing to commit the time or lacking the stomach to buy and hold dividend stocks directly would be wise to evaluate such funds for their portfolios.

However, they lose a valuable benefit: control.

Specifically, almost all ETFs own dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of stocks. Vanguard’s High Dividend Yield ETF (VYM) owns over 350 companies, for example.

Some of these are good businesses with safe dividends, while others are lower in quality and will put their dividends on the chopping block. Some have high yields, others hardly generate much income at all.

Simply put, an ETF is a hodgepodge of companies which may or not match your own income needs and risk tolerance very well.

Vanguard’s High Dividend Yield ETF got into trouble during the financial crisis because it was not focused on dividend safety. The ETF’s dividend income dropped by 25% during this period and took four years to recover to a new high.

Hand-picking your own dividend stocks with a focus on income safety can deliver higher, more predictable, and faster-growing income compared to most low-cost ETFs. You will also better understand all of the investments you own, helping you weather the next downturn with greater confidence.

However, there are several risks to be aware of when it comes to living on dividend income in retirement.

Risks of Living on Dividend Income

However, asset allocation depends on an individual’s unique financial situation and risk tolerance.

A primary investment objective in retirement is to guarantee a minimum daily standard of living so you don’t outlive your nest egg and can sleep well at night.

Some folks are able to meet that minimum income amount they need through some combination of pension income, Social Security payments, and guaranteed interest from certificates of deposit.

In those cases, these investors might allocate upwards of 80-100% of their portfolio to dividend-paying stocks to generate more income and achieve stronger long-term capital appreciation potential and income growth. Your asset mix between bonds, stocks, and cash will ultimately be driven by the income you need to generate and your risk tolerance.

While this goes against traditional asset allocation advice in retirement, which calls for holding a more balanced mix of stocks and bonds (plus 2-3 years of living expenses in cash), these retired folks view their guaranteed Social Security and pension payments as their “bond” income. Therefore, they are comfortable investing more heavily in stocks.

Going more into stocks (even higher quality dividend stocks) will increase your portfolio’s volatility compared to owning a mix of Treasuries and stocks. The upsides are that you will generate more income, that income will grow faster (Treasury payments are fixed), and your portfolio will have much greater long-term potential for capital appreciation.

However, your short-term returns will be less predictable, which can be troublesome if you need to periodically sell portions of your portfolio to make ends meet in retirement or don’t have a stomach for much volatility. A return of 0% from bonds becomes a lot more attractive if your stock portfolio drops by 25%.

Another way you could run into trouble with a dividend strategy is by only owning high-yielding stocks concentrated in one or two sectors, like real estate investment trusts (REITs) and utilities. Should interest rates rise and trigger a major investor exodus in high-yield, low-volatility sectors, significant price volatility and underperformance could occur.

Dividend investors can also fall into the trap of hindsight bias if they are not careful. The desire to own consistent dividend growers has caused groups of stocks like the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats Index to become wildly popular with investors. Dividend aristocrats are stocks in the S&P 500 that have increased their dividend for at least the last 25 consecutive years.

These stocks get the attention of dividend investors because they have outperformed the market and we like to assume that many of them will always keep paying and growing their dividends, which is far from guaranteed. Look at General Electric or AIG prior to the financial crisis as examples.

Clearly, it is important to diversify your holdings and remember that you own shares of stock, not bonds. If a company fails to pay back its debt, it files for bankruptcy. If business conditions get tough, it will simply cut the dividend first to stay alive. Generally speaking, stocks and their dividend income are riskier than bonds. There is no free lunch.

However, many of us would prefer to leave our principal untouched and live off the dividend income it generates each month, even if it results in a somewhat lower total return. While this mentality is irrational, it can also create a desire to chase high-yield dividend stocks. In many cases, it is a big mistake to simply reach for dividend stocks that match your yield objective.

Unfortunately, many stocks (excluding some REITs and MLPs) with dividend yields greater than 5% are signaling that something could be structurally wrong with their businesses or that the dividend will need to be cut to help the company survive. In these situations, your principal often faces the greatest risk of long-term erosion.

You must always understand what is enabling the company to offer such a large payout. In our opinion, investors are usually better off pursuing lower risk stocks that yield 5% or less. These companies tend to have better prospects of maintaining and growing earnings and investors’ principal over time.

Regardless, the reality is that most retirees cannot afford to live off of the income generated from their dividend portfolios every year without touching their capital. These investors should especially focus on designing a portfolio for total return rather than for dividend income alone.

Once the portfolio’s objectives and stock and bond allocation are determined, you can figure out how to get the cash flow out of it, whether it’s through asset sales, interest payments, dividends, or something else. Dividend payments are one important way to generate consistent cash flow, but they shouldn’t be looked at in a vacuum. Keep your mind open and be aware of alternative income sources that might be an equally attractive fit for you.

Additional downsides to dividend investing are the time it requires to stay current with your holdings and the learning required to get started. While investing isn’t rocket science, it does require a stomach for risk (i.e. price volatility), enough financial literacy to understand the basic guts of a company, a commitment to stay current with the quality of your holdings, and common sense.

Of course, this also assumes that the individual investor can find safe dividend stocks that perform no worse than the dividend mutual funds and ETFs that are available.

Closing Thoughts

With every decision, be sure to thoroughly review the fees, flexibility, and fine print of the investment vehicles you are considering. At the end of the day, remember that you are looking to meet a consistent cash flow objective and are not wedded to achieving your goal through any one source such as bond interest, annuity payments, or dividend income.