In 2011, my parents gave me a sum of money that was both outrageous and, in the real estate terms of major cities, quite reasonable: 10 percent down on the 250-square-foot apartment I still own in Fort Greene, Brooklyn. While I was conflicted about taking it, there wasn’t much of a question about whether I’d accept. My writing career (any writing career!) was inherently unstable; having a roof over my head that I could not only count on but would also help me build equity meant everything. And though I pay my monthly maintenance and mortgage on my own, as I did with my rent, that initial down payment would have taken me years to save, time that would have priced me out of the market.

“We’d leave you this money anyway; you might as well use it now!” my dad would say in conversations about how I should buy, and I’d remind him that he and my mom were never supposed to die. After I closed on my apartment, I’d gently correct people who asked if I’d mind telling them what I paid in rent that um, I actually owned, but I didn’t tend to divulge how I owned, exactly. Only my good friends, and those who asked point-blank, knew that.

I, like any savvy internetter, know full well how outrage against privilege (financial or otherwise) works: We railed against the entitled Refinery29 Money Diarist whose parents not only paid her rent, but who also gave her an allowance, supplemented by a second allowance from her grandfather. On the other side of the coin is Kylie Jenner, touted as self-made, at least according to that July Forbes cover, and very close to billionaire status. We railed against that, too, but for a different reason: “It is not shade to point out that Kylie Jenner isn’t self-made,” tweeted the writer Roxane Gay. “She grew up in a wealthy, famous family. Her success is commendable but it comes by virtue of her privilege.”

In the wake of the Refinery29 outrage, Jared Richards tweeted, “if your parents pay your rent, you have to put it in your Twitter bio,” garnering nearly 70,000 likes. But actually opening up these dialogues around money, privilege, success, and class is as complex as the threads weaving those four beasts together. Privilege is in part defined by where each of us stands; how we look at other people—whether it’s through their Instagram feed or the windows of their brownstone—involves our own psychology, experience, and situation in life. I’m no Kylie Jenner, but getting the down payment for your New York City apartment is as unimaginable to many as being a Kardashian is to me. Sure, it’s better for everyone to “just be honest,” but what does the truth actually look like?

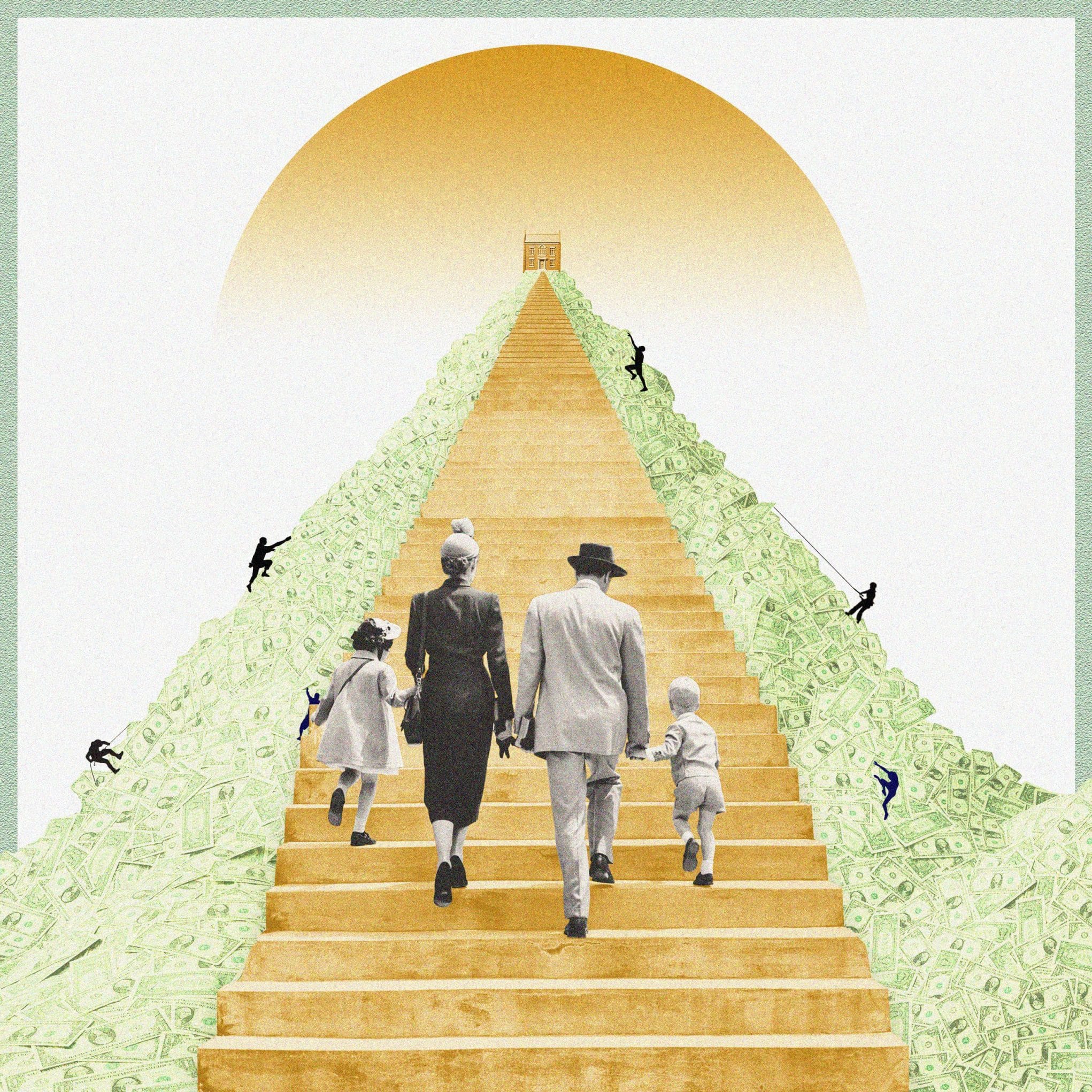

Take a look around you at the lives you envy, the ones that make you boil with resentment, or fill you with insecurity about your own subpar existence: That adorable Brooklyn brownstone or chic-but-rustic upstate home; the career that YOU want (and you should have, what are you doing wrong?); the impeccable wardrobe; the mid-century modern furniture; the international vacations; the time spent flitting between gorgeous hotels or going to boutique fitness classes or (seemingly) not working at all. Maybe it’s simply an ease of life indicating that whoever possesses it has been better at this game than you have. But how does anyone start their own company or buy a home, much less travel to Fiji, in a time of crushing student debt, when the job market is shifting at an out-of-control rate into a soulless gig economy, industries are dying left and right, we’re totally burning out, and we’re being replaced with robots. Health care costs are rising faster than you can make a doctor’s appointment, but that’s OK, because robots don’t get sick.

The writer and podcaster Gaby Dunn has a new book called Bad with Money: The Imperfect Art of Getting Your Financial Sh*t Together, a look at her own financial history and what she’s learned, along with thoughts on what we can all do better. “Everything is so broken!,” she tells me. “You hear about so many problems with medical debt, people being unable to buy a house, people saddled with student loans, the job market. It seems insurmountable. It’s hard for one person to make it out of the muck without a big systemic overhaul to help everyone else.” Meanwhile, in the penthouse upstairs, or perhaps on social media, people appear to be having the most glorious time. Is the Titanic sinking while the band plays on, or are some people just better with money?

As with any “meritocracy,” appearances are only a piece of the story. Wealth inequality has increased more in this decade than any other in American history, while economic mobility has done the opposite, as Matthew Stewart writes in an Atlantic article about the new American aristocracy. Money has always been passed down in families, but today, across America, parents who can are helping their grown children at unprecedented levels. A recent study from Merrill Lynch and Age Wave reported that 79 percent of the parents surveyed are providing financial support to their adult children, at an average $7,000 a year—making for a combined $500 billion annually. Increasing numbers of first-time home buyers in the U.S. are getting money from their parents for down payments. In a CreditCards.com survey of parents with children over the age of 18, three out of four helped their kids pay debts and living expenses, including rent, utilities, and cell phone bills. The help continues in death; roughly 60 percent of America’s wealth is inherited, though this, like the rest of privilege, skews heavily white: According to the authors of a 2018 study published in the American Journal of Economics and Sociology, the average inheritance for white families is over $150,000; for black families, it’s under $40,000.

Of course, helping your kid by providing a college education or paying a cell phone bill, or even paying for them to go on an extravagant vacation with you, is a far cry from leaving them $11.4 million (the amount rich folks can bequeath their kids tax-free in 2019). And, by the way, none of this means that children who accept help from their parents are lazy or entitled. Consider Daniella Pierson, 23, the founder and CEO of Newsette, a mini-magazine with 400,000 subscribers that she started when she was a sophomore at Boston University. When Pierson hit 100,000 subscribers a year in, she went to her parents, who run several successful car dealerships, with a business plan, asking for money. “They were reluctant. They’re completely self-made,” she says. Finally, they agreed to give her $15,000—a loan, with 5 percent interest. “After I graduated, we made over $25,000 in one month, and I wrote them a check,” Pierson says. “I was done with my loan.” Even though $15,000 is a comparatively small investment, her biggest fear was hearing “she’s only successful because of her parents.” Pierson admits, however, that there are multiple factors in anyone’s success: Her parents paid for her college tuition, and she was able to stay on their health insurance while building her business. Most of all, she had her parents as inspirations. “That’s really where my work ethic comes from,” she says.

Farnoosh Torabi, creator and host of the “So Money” podcast and author of When She Makes More: 10 Rules for Breadwinning Women, was able to graduate from college debt-free and buy her first home with the help of her parents. “I’m grateful that my parents gave me a head start, but I’m going to give myself the credit where it’s due,” she says. “I had the responsibility and appreciation for that and took it to the next level. If you look at the other side of the equation, there are plenty of people who came from privilege and are doing crap!”

At the same time, having the option of taking risks—for me, that meant quitting a job with health benefits to become a full-time freelancer after I sold my first book—relies on a certain amount of base level stability. You’ve got backup, or, as another journalist friend of mine who also bought an apartment with the help of her parents put it, “If money gets really tough, I know I can always move somewhere cheap and rent my place.” Ross Levine and Yona Rubenstein, economists at University of California, Berkeley, and The London School of Economics, wrote a paper about the shared traits of entrepreneurs in 2013. Guess what? Most were white men who were highly educated, i.e., from a certain class of privilege. Levine told Quartz, “If one does not have money in the form of a family with money, the chances of becoming an entrepreneur drop quite a bit.” (In their working paper, they explain how a “$100,000 increase in family income is associated with a more than 50 percent increase in the odds of becoming incorporated self-employed.” Further, according to Quartz, “the average cost to launch a startup is around $30,000,” and “more than 80 percent of funding for new businesses comes from personal savings and friends and family.”)

This flies in the face of the idealized rags-to-riches American success story, that it’s not only possible to pull yourself up by your bootstraps, it’s also the most honorable and worthy storyline there is. Which is why disclosing the truth about how you—or who—really funded your first business, home, or even something as simple as your first car is so important. Not sharing the whole truth can cause anxiety among those who don’t have such resources; beyond that, misplaced expectations about success and achievement can lead to disappointment and even depression. And while there’s nothing wrong with getting help from your parents, keeping it under wraps takes away from the even harder-won successes of those who truly came from nothing. “Financial anxiety is the biggest crisis in America,” says Bea Arthur, a therapist and entrepreneur who just launched her third company, The Difference, Amazon’s very first Alexa skill for therapy. Arthur’s first business was started, she says, with a check written by her boyfriend at the time. “And that was not the last check,” she says. “I’m a really hard worker … but none of that could have been paid [for] if I didn’t have a rich old white boyfriend. It doesn’t just take grit.”

In a way, you can’t really blame people for being a bit cagey about where they get their cash. Discussions about money and class remain one of the last taboos in American society, in part because it feels uncomfortable to insert into a conversation, but also because there’s a certain amount of shaming that comes with it—or just the fear of shaming, which is equally real. And the judgments tend to be harsher for women than men. “People who come from privilege are often discouraged from talking about the fact, it’s perceived as bragging,” says Clelia Warburg Peters, president of Warburg Realty. “Our country was built on the backs of men who inherited money from their fathers, but somehow a woman who inherits, she’s just a spoiled rich girl.” Growing up, Peters inhabited a particular New York City sphere of affluence, attending Chapin and then Yale. After graduation, she did humanitarian relief work before getting her MBA and, in 2014, she joined the family business. “I’ve worked hard to earn my place and respect,” she says. “But a lot of the time I had access to those opportunities for reasons that were more complex than me being deserving. … Without acknowledging the fact that you come from a place of privilege, you’re reinforcing the power of the idea that it doesn’t make a difference.”

I turned to an editor friend for a frank conversation about how I bought my apartment. She told me, “I was curious, but I don’t know how a single person in America who doesn’t have family money could buy anything, I really don’t, if they’re not working in finance or they’re not a doctor. ” And, she pointed out, while it’s OK (at least in New York City) to ask intrusive questions about what people pay for rent—always framed as “I’m in the market, do you mind sharing?”—asking how they bought is a whole different thing. The divulging we tend to do usually occurs with people of the same class, or who appear to be the same class, which, unfortunately, does nothing to break down those barriers to access that Peters mentions.

“There’s this idea that getting help is somehow cheating,” my journalist friend told me. She and I figured out we each owned our places, thanks to our parents, around the same time—I remember seeing hers and wondering how she could afford it—and, she says, “I do think it contributed to my feeling that I can be financially honest with you.” Back when she was first starting out, to avoid any awkwardness, she avoided inviting friends over. But “cheating” isn’t really accurate, she muses. “It would be true if life were, like, a foot race or game with concrete winners and losers … but it’s actually just a mess of people doing the best they can in whatever way they can, with a million different factors and conflicting impulses.”

So, radical honesty: Who’s taken money from their parents in some way or another? Quite a few of us, from writers like me to Instagram influencers to successful entrepreneurs. That doesn’t mean there isn’t a lot of hard work, or talent, in those tales.

But there’s luck, too. Journalist Charlotte Cowles, who writes about money for The Cut, went to Columbia University, where everyone lived in dorms. Once she graduated, she saw the friends she’d known divide into two different groups: those who could get an apartment in Manhattan, and those who had to move home and look for a job. “My parents were able to help with a deposit on an apartment that I shared with three other people. … There’s a big part of me that’s like, would I have made it in this career if I had student loans and no way to be in New York City after I graduated from college? I really don’t know.”

Anthony Casalena lived at home after college, but his story is a little bit different. He’s the 36-year-old founder and CEO of Squarespace, which he started in 2003 from his dorm room at the University of Maryland — and which is now worth $1.7 billion. “To launch in January of 2004, the only thing I couldn’t do is buy the servers, and I can’t draw logos, so I needed help with that,” he tells me. “That was when I turned to my parents.” They gave him $30,000, and he gave them part of the company. When he graduated in 2005, he moved home for 6 or 7 months while he paid off his credit card debt, and then moved to New York City. The money “has always been a part of my story, I’ve never tried to hide it,” he says. “Anyone who has had some level of success, you’ve got to consider yourself lucky. I’m lucky that I grew up around computers, that my parents were able to provide that. But Squarespace also involved a massive amount of hard work.” As for his parents, “They’re still shareholders,” he says. “It’s the best investment they ever made by a factor of like 1,000!”

The help that Katharine Bolin, 30, got was her parents paying for her college education outright, which her dad worked the night shift at IBM to do. That’s how she was able to start Sweet Reach Media, the digital marketing and PR business she runs in Minneapolis, which is on track to make six figures this year. “I am forever grateful to my parents and still thank them every time I see them,” she says. “I can’t imagine I would be in the same position I am today if I had to pay $500 or month or more in student loans throughout my twenties.” Her parents also did “little things, like they would pay for my cell phone. That makes a huge difference.”

Caroline Moss, co-author of Hey Ladies!: The Story of 8 Best Friends, 1 Year, and Way, Way Too Many Emails, tells me that if her parents hadn’t paid for her college education, she wouldn’t have the career she does right now. “There are people who’ve worked really hard to get where they are, but have also gotten where they are because of a leg up. And maybe there’s not a ton of understanding that some people will never get the opportunities that you have, because they’ll never be able to do a free internship, or they’ll never be able to afford to live in New York City.” There’s also a part of her that’s jealous when she looks at someone her own age who’s already bought a house. “Then I find out it was a gift, they inherited money, and I’m like, Oh, OK, it’s not even worth comparing. … I don’t think they should be humiliated, but if it’s just the truth, I didn’t pay for this, it makes me feel better.”

In her first book, You’re So Money, Farnoosh Torabi revealed that her parents had helped her with her first home purchase. She tells me she faced some criticism around that, with people saying that she hadn’t really struggled. Her parents’ assistance arguably put her on a path in which she was able to take the leap of faith to write that book, which led to so much more—including helping others by advising them about their own financial choices and realities. It goes back to that relationship between stability and risk-taking; having the time and space (and cash) to invest in that dream career that might not ever pay off; getting access to those first, essential resources to put into something you’ll grow into so much more. “Regardless of how much privilege you have, if you don’t do the work, it’s not gonna happen,” Cowles says, “but having the privilege to direct your work into what’s going to pay off for you in the future, that’s a lot of privilege.”

The combination of her parents’ help and her own work ethic meant “I ended up being able to really get ahead in my life,” says Torabi. “You have to be comfortable with the beginning, middle, and end of that story.” Sure, a lot of people are only going to see the headline; that’s just how it works—but, she notes, you’re doing a bigger service by being honest about the whole truth.

Lisa Przystup has the most beautiful Instagram account, @brass_tacks, featuring the kind of pictures you want to live in, the country house, the trips to Japan and Jackson Hole. She also frequently thinks about the half-truths of social media. “We still [rent] in Brooklyn, and a reason we could afford the house upstate is my husband’s dad helped us with the down payment,” she says. (They’re paying him back every month, with interest.) “That’s a lot to unload in an Instagram caption. Should I try to be like, ‘Upstate for the weekend, not here full-time, wish we could be’?” She pauses. “I guess ultimately, the question is, how are you honest about the life you’re leading in a way that levels the playing field and doesn’t set people up for unrealistic expectations about what they should be doing?”

“It’s really lovely to be realistic about what’s possible,” says holistic facialist Britta Plug, who was able to open Studio Britta in New York City thanks to a $50,000 loan from her parents (and her own $50,000 in credit cards). “I have zero shame,” she says. “I’m just incredibly grateful. … With the cost of living in this town, there’s no way I could have opened a place without help.” Plug knows borrowing from your parents isn’t a choice everyone can make, and supports asking and answering the question, How did you make this happen? “Then you don’t have to feel bad about yourself for not being able to do it.”

Not talking about it reinforces the status quo, as Clelia Peters explains. “In any structure of privilege, it’s incumbent on the people at the top to start to examine their privilege and also grapple with the way their privilege may mean that other people are put in less privileged positions. … That’s why it’s so dangerous when people don’t talk about it.”

There’s a degree of braveness that comes of being outspoken about your financial story, says Torabi, who recommends starting with the people you trust—those who deserve to know—and getting them to share, too. But before that, have a conversation with yourself. Ask yourself, “What is the story about my money that I believe in, appreciate, and think is worth telling?” she says. “You have to be OK with people raising their brow at that.” Don’t take it for granted; have it be fuel for your motivation. “Tell us the whole story, don’t lie, and put it in context,” for example, “You graduated from college, and you want to put something on Instagram. Say, ‘I’m graduating debt-free, thanks, Mom and Dad, for using your 401K to put me through college!’”

There’s a caveat for all of us: “If you’re going to say we should have transparency about money, it goes the other way, too,” says Gaby Dunn, the author of Bad with Money: The Imperfect Art of Getting Your Financial Sh*t Together. “If someone shares that they get money from their parents or their salary is high … there’s nothing that the internet wants to go to town on more than that. But you can’t encourage people to talk about it and then shit on them when they do.”

Talking’s just a first step, to be sure. As we come to terms with the inherent financial inequities in society, which trickle down not only to burgeoning billionaires but also to freelance writers and their Brooklyn apartments, there’s plenty more to do to help break down the invisible barriers that keep some people out. As Caroline Moss tells me, “I think it’s more of a question of, are people who are afforded the privilege of getting help going to help others? … If you have the privilege of not having to pay 50 percent of your rent because your parents are paying, how can you advocate for interns to make a decent-enough salary, or for scholarships to support an intern or fellow? That’s where the change comes in.”