It’s a bright September morning in San Carlos, California, and Masayoshi Son, chairman of SoftBank, is throwing me off schedule. I’d come, as he had, to meet with the people he’s tapped to run the Vision Fund, his $100 billion bet on the future of, well, everything. After almost four decades of building SoftBank into a telecom conglomerate, Son, an inveterate dealmaker, launched this unprecedented venture two years ago to back startups that he believes are driving a new wave of digital upheaval. He has staked everything on its success–his company, his reputation, his fortune. We’d both arrived with the same basic question: Where is this massive vehicle heading? But because I wasn’t the one footing the 12-figure allowance, I understood that I’d be the one to wait.

In the hubbub of Son’s visit, my 9 a.m. meeting gets rescheduled multiple times until it’s set for 4:30 p.m. When I finally arrive at the Vision Fund’s offices, just off California’s Highway 101, I’m struck by how mundane they are. Son is known for big, showy statements. He reportedly paid $117 million for a home in Woodside in 2013, the highest price ever in the U.S. This glass and concrete building, on the other hand, could be found in any part of suburban America.

The room where I wait is spartan. There is an empty desk in one corner, and a conference table with a fake-wood veneer. I try to read the pale gray scribbles on a whiteboard, hoping they might shed light on what happens in this place, but the surface has been too well scrubbed. The interior glass walls of the conference room have been lined with a white, papery substance that turns anyone on the other side into apparitions.

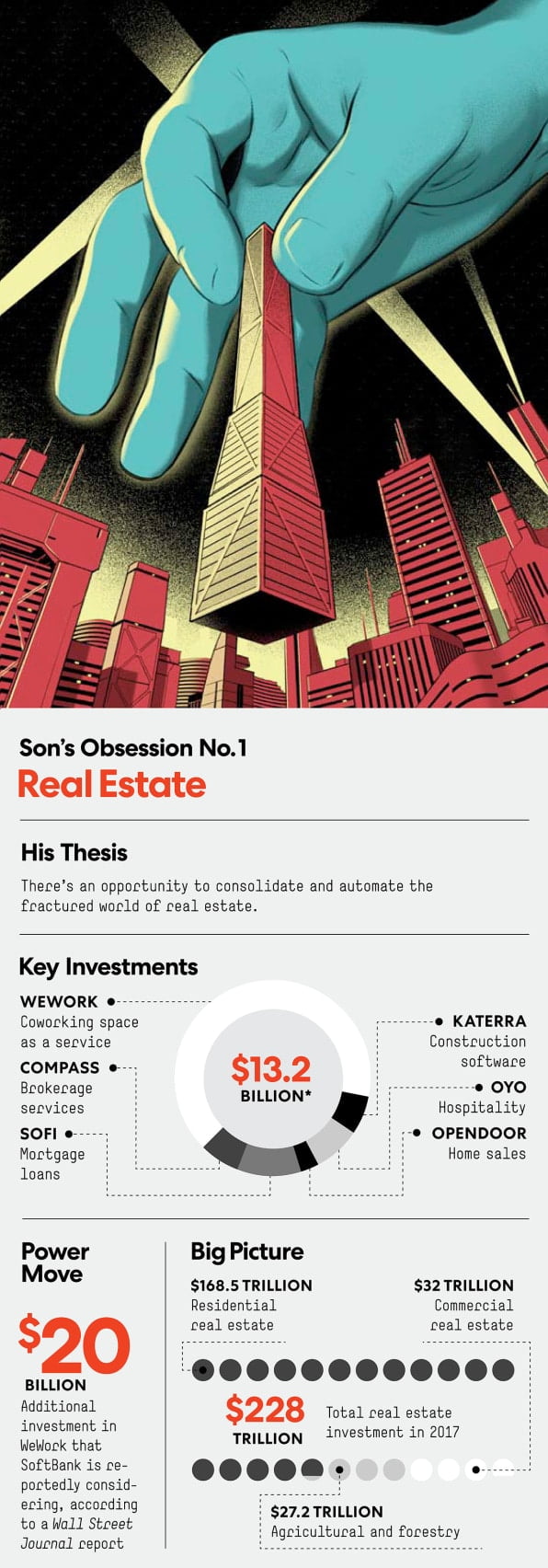

Finally, Rajeev Misra, CEO of the entity overseeing the Vision Fund, rushes into the room, smiling broadly and apologizing profusely. Misra, who has flown in from London for these meetings, looks exhausted but jacked up, as if he’s gotten a shot of adrenaline. Son has this effect on people. It is an exceptionally busy day at the Vision Fund. Not only is the big boss in from Tokyo, but unbeknownst to me, the team is preparing to announce billions of dollars in new investments: a $1 billion round for Oyo, the Indian hospitality startup; $800 million split evenly between Compass and OpenDoor, two real estate disrupters; $100 million for Loggi, a Brazilian delivery startup. It also would lead a $3 billion round in Chinese startup ByteDance, which makes several popular news and entertainment apps, including TikTok. At the same time, Son and his partners are in the midst of launching a second $100 billion fund, with plans already underway to raise an additional $45 billion investment from Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia—the Vision Fund’s primary backer. Neither Misra nor I knew it then, but this relationship would soon get complicated.

“So what do you want to know?” Misra says, clapping his hands loudly. “You want the road map? I’ll start from 10,000 feet. . . .”

On the surface, the story of the Vision Fund is about money. How could it not be? The numbers are eye-popping. The Vision Fund’s minimum investment in startups is $100 million, and in just over two years since its October 2016 debut, it’s committed more than $70 billion. Son, 61 years old, will also back companies he likes via SoftBank itself or other means: He’s put some $20 billion–and counting–into Uber and WeWork through a combination of financial instruments. (Son’s machinations have always been highly complex and it’s not worth getting lost in the minutiae; regardless of the means, the deals are at his behest.) His big-money bets agitate the venture capitalists who have long inhabited the dry stretch of lowlands between San Francisco and San Jose, a place where any fund over $1 billion was head-turning as recently as three years ago. Turns out, nobody likes competing with a bottomless-pocketed behemoth. “Have you seen the movie Ghostbusters? It’s like the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man tramping around,” one VC tells me before I visit SoftBank. Then he asks me to ask Misra the question everyone in town wants to know: Who is Son investing in next?

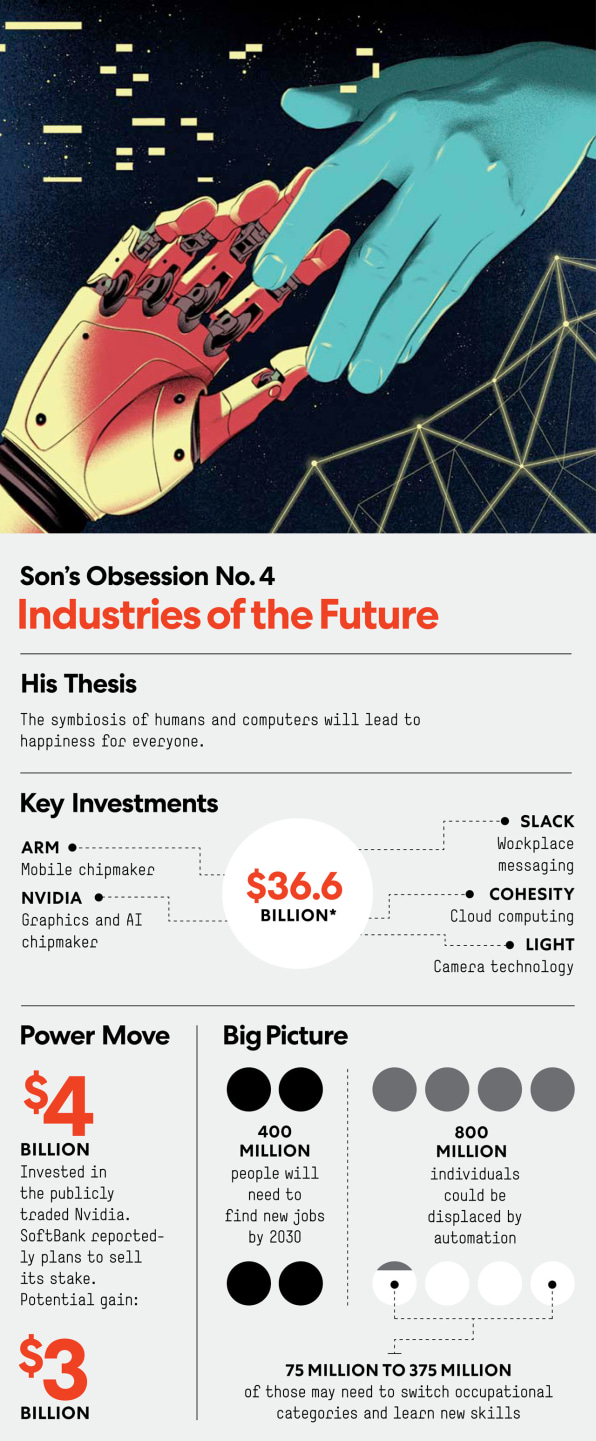

Underneath, though, lies a more complex story. Computers, Son believes, will run the planet more intelligently than humans can. Futurist Ray Kurzweil coined the term “the singularity” to describe the moment when computers take over—and he predicts it will be here by 2040. The Vision Fund could move up this date. And Son is pouring unprecedented amounts of capital into the people and companies employing artificial intelligence and machine learning to optimize every industry that affects our lives—from real estate to food to transportation.

When Son first detailed his vision, during an investor presentation in 2010–slides depicted chips implanted in brains, cloned animals, and a human hand giving a robotic one a valentine–there were plenty of scoffs. Many see this machine-driven future as frightening, or even dystopian. But Son believes that robots will make us healthier and happier.

He has long told people, “I have a 300-year plan,” and that declaration is not just the fantastic ambition of a billionaire. He has the means to pursue these dreams, and they’re starting to become very real. He is one of the few people with the power to make decisions that could have global consequences for the future of technology and society for decades, if not centuries. As Facebook and Google have demonstrated, machines take on the attributes of their makers. Algorithms, software, and networks all have biases, and Son likes to bet on founders who remind him of himself, or at least share his ideals. Son’s values, then, will become our own, dictating the direction of this machine-powered world.

So where is this massive vehicle heading?

Our story begins with a dinner Son hosted one summer night in 2016 at his nine-acre estate in Woodside. The table was set in the garden so the guests could enjoy the crisp summer air of a northern California evening, as well as the breathtaking hilltop views of San Francisco horse country.

Among the attendees was Simon Segars, who had no idea when he sat down to eat that this would be one of the most important events of his life. Segars, CEO of chip designer Arm, had imagined that he might win some new business from Son–perhaps SoftBank would agree to put Arm’s chips in the cell phones it sells through its telecommunications businesses. He didn’t fully appreciate at that moment that one of his dining companions, Ron Fisher, has been one of Son’s trusted consiglieri for more than 30 years and is almost always present when Son is considering a major deal. “We started talking about AI and all these future-looking technologies,” Segars recalls, and Son grew visibly animated. They discussed how Arm’s technology could be used to turn anything–tables, chairs, refrigerators, cars, doors, keys–into a wired object. Son pressed Segars: If money were no constraint, how many devices could his technology create? As the leader of a publicly traded company, Segars had never been asked to think this way before. “I remember Simon’s eyes getting very wide,” Fisher recalls.

A few days later, Segars was at his desk when a call came from Tokyo: It was Son, who said he needed to see him and Arm chairman Stuart Chambers right away. Chambers was on vacation, on a yacht off the Turkish coast, but Son didn’t want to wait. He sent a private jet to fetch Segars and persuaded Chambers to dock his boat in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The day unfolded like a scene from a James Bond movie: Segars landed at a small airstrip near the village of Marmaris, Turkey, where two security men picked him up and whisked him to an empty restaurant overlooking the marina. (Son had arranged to have it cleared of other customers.) “It was surreal,” Segars says.

Son got right to it: He wanted Arm and was willing to pay for it. In a deal that would astound Wall Street for its speed and audacity, SoftBank offered $32 billion for the company, 43% more than its market value at the time. Son negotiated and closed the deal in two weeks. A photo of that trip to Turkey shows Son standing by the port of Marmaris, boats bobbing on the sea behind him. He is smiling, as though he knows how big this moment is.

To pursue his sweeping vision of interconnecting everyday objects to create intelligent machines, Son would need more money. So he created the Vision Fund. The first investor was the Saudi Arabian Public Investment Fund, with a $45 billion commitment that October. It’s hard to overemphasize the significance of the Saudis coming in at this stage. The entire global venture capital industry invested just over $70 billion annually, so the idea of a single $100 billion fund seemed fantastical. The move conveyed such confidence in Son’s vision and ability to execute on it that it quickly attracted other investors, such as Apple, Foxconn, and Qualcomm. By the following May, the fund had secured $93 billion. As Son explained at the time, he needed this much capital because “the next stage of the Information Revolution is underway, and building the businesses that will make this possible will require unprecedented large-scale, long-term investment.” Now he was ready to start what Bloomberg has called “an all-out blitz on the heart of Silicon Valley.”

When I step off the elevator at WeWork’s headquarters in New York City one Thursday morning in October 2018, a dozen or so children have taken over the reception area. They’re students from WeGrow, an elementary school the company launched a year earlier, and they’re hosting their weekly pop-up vegetable stand. “Would you like to buy something?” asks a girl of around 6 or 7, holding an iPad listing products and prices. I’m here to learn how Vision Fund’s money is being spent and would rather not walk into my meetings holding a head of lettuce, so, feeling like the Grinch, I tell her I’ll pick something up on the way out. She shrugs; there are plenty of other customers.

Sunlight pours in through tall windows overlooking West 18th Street. The open floor plan lets me see from the reception area across rows of tables populated by WeWork members tapping away on laptops. At the far end of the space, there’s a wall of glass, behind which Adam Neumann, WeWork’s CEO, is taking a meeting. He looks like a rock star, with long, dark curls brushing his shoulders, black jeans, and a wide-brimmed black fedora, and as far as the Vision Fund is concerned, he is. “There is a sense of massive opportunity,” says Fisher, who sits on WeWork’s board. Son has even called WeWork his next Alibaba. In 2000, he put $20 million in the untested Chinese commerce startup. Today, Alibaba’s market cap is nearly $400 billion.

WeWork’s potential lies in what might happen when you apply AI to the environment where most of us spend the majority of our waking hours. I head down one floor to meet Mark Tanner, a WeWork product manager, who shows me a proprietary software system that the company has built to manage the 335 locations it now operates around the world. He starts by pulling up an aerial view of the WeWork floor I had just visited. My movements, from the moment I stepped off the elevator, have been monitored and captured by a sophisticated system of sensors that live under tables, above couches, and so forth. It’s part of a pilot that WeWork is testing to explore how people move through their workday. The machines pick up all kinds of details, which WeWork then uses to adjust everything from design to hiring. For example, sensors installed near this office’s main-floor self-serve coffee station helped WeWork discern that the morning lines were too long, so they added a barista. The larger conference rooms rarely got filled to capacity–often just two or three people would use rooms designed for 20–so the company is refashioning some spaces for smaller groups. (WeWork executives assure me that “the sensors do not capture personal identifiable information.”)

“We can go to Berlin,” Tanner says, tapping another monitor. He’s now using Field Lens, project-management software that WeWork acquired in 2017. Field Lens helps WeWork track building construction and maintenance. A live image appears. Zooming in, Tanner shows me how the system can pick up granular details about a site. We’re 4,000 miles away, but I see a nail sticking up from a floorboard. “We’ll have to get someone to fix that,” he says nonchalantly.

I ask what else we can spy on. He taps the screen and calls up a large map displaying each of the 83 cities in which WeWork operates. From here, we can drop down into any of them: Around the world in 80 nanoseconds.

“Basically, every object will have the potential to be a computer,” adds David Fano, WeWork’s chief growth officer, who is overseeing development of this new technology. “We are looking at, what does that world look like when the office is this highly connected, intelligent thing?”

This is why Son is investing billions in WeWork. As of mid-December, the tally was up to $8.65 billion (including debt and funding of subsidiaries), and the real estate company was valued at $45 billion. [In early January 2019, SoftBank invested another $2 billion.] To meet Son’s lofty expectations, WeWork is spending as fast as it can to spread its footprint. It has more than doubled its locations in the 15 months since SoftBank’s initial investment, and WeWork has acquired six companies and invested in another half dozen. It has grabbed so much office space that it is now the largest commercial tenant in New York City, Washington, D.C., and London. It has expanded into Brazil and India. In the fourth quarter of 2018, the company planned to add more than 100,000 desks. This pace may only accelerate: SoftBank is in talks to take an even larger stake in WeWork for up to $20 billion, according to a source familiar with both companies.

These moves have accelerated WeWork’s revenues but also its losses. In the first nine months of 2018, WeWork shed $1.22 billion, even as it grossed $1.25 billion. The company owes $18 billion in rent from office space it has leased. When WeWork issued bonds last spring to raise another $700 million, ratings agencies labeled them of lower quality, aka junk. “We cannot get comfortable with the company’s financial and operating position, which includes a massive asset/liability mismatch that is usually a recipe for disaster, significant cash burn, cyclically untested real estate business model, and uncertain path to profitability,” CreditSights analyst Jesse Rosenthal wrote at the time. The price of those bonds dropped almost 5% below their list value in their first five days of trading, a signal of investor skepticism.

As a result of WeWork’s hypergrowth, both physical and technological, the company is increasingly viewing itself less as a real estate company than “a spatial platform,” helping connect humans with intelligent machines. A 2018 internal WeWork presentation depicted the scope of the company’s aspirations as a series of concentric circles. On the outermost ring sit its actual business units, from its school to its gym to its live events (such as its annual adult summer camp, a mashup of the Governors Ball Music Festival, Bhakti Fest, and Burning Man). The next layer is the fundamental elements of human existence–live, love, play, learn, and gather–which those products seek to fulfill. Then, at the very center: We.

Neumann has always been the kind of entrepreneur who thought about having 100 buildings when he had three, but with Son backing him, WeWork’s expansion has been extraordinary. “Adam and Masa have a special relationship,” says Artie Minson, WeWork’s CFO. Those who work closely with them say Son sees in Neumann a younger version of himself–hungry and willing to move at top speed. Those inside WeWork say that Son’s mentorship has been critical. “He’s helped us move from asset-based thinking, how a building is performing, to how an account is performing,” says Fano, who joined WeWork in 2015 when the company acquired his building management startup. WeWork’s aim, he explains, is to “shed ourselves of any remnants of being like a real estate company.”

“Masa wants to meet with you. Can you get on a plane tomorrow?”

For many, the call to Tokyo comes out of the blue, as it did with Stefan Heck, founder and CEO of Nauto, a startup that builds AI-powered cameras to enable self-driving vehicles. Heck had been preparing for a board meeting and was reluctant to cancel it, but one of his board members told him to get going, saying, “People spend their whole lives trying to get a meeting with Masa.”

Every entrepreneur who receives money from the Vision Fund eventually sits down with the SoftBank boss. The Vision Fund’s 11 partners (based in California, London, and Tokyo) decide which entrepreneurs are ready at a weekly meeting, after months spent getting to know a company and its founders. Usually, CEOs are ushered into a large conference room atop SoftBank’s sleek Shiodome tower in Tokyo, which has expansive views of the harbor and beyond, a metaphor for how Son searches wider than almost all other venture capitalists for his investments. One of Son’s Vision Fund VCs, Jeffrey Housenbold, ex-CEO of the photo service Shutterfly, is leading an effort to build a system to track emerging startups, which he hopes will help the fund identify its next investments even faster and more efficiently.

Son is small in stature and soft-spoken. Those who know him well say he’s quick-witted and humble, with a self-deprecating sense of humor. When friends teased him about his vague resemblance to Charlie Brown, he put a Snoopy doll on his desk. One time, at an investor conference, he called himself “big mouth.” He loves the movie Star Wars. “Yoda says, ‘Listen to the Force,’ ” he told an interviewer, who asked him in May 2018 how he makes his investment picks. He rarely wears suits. When Nauto CEO Heck met Son for the first time, Son was dressed in jeans and slippers. “I have seen young founders come in very apprehensive to meet Masa,” says Fisher, who is often with Son during these pitch meetings. “By the end they are talking to him about their dreams.”

Colleagues say Son is at his happiest when chatting with startup founders–brainstorming, strategizing, inventing. “If Masa could spend the whole day doing what he loves, it would be meeting with entrepreneurs,” says Marcelo Claure, SoftBank’s chief operating officer and the former CEO of Sprint (the wireless carrier that boasts SoftBank as its majority owner).

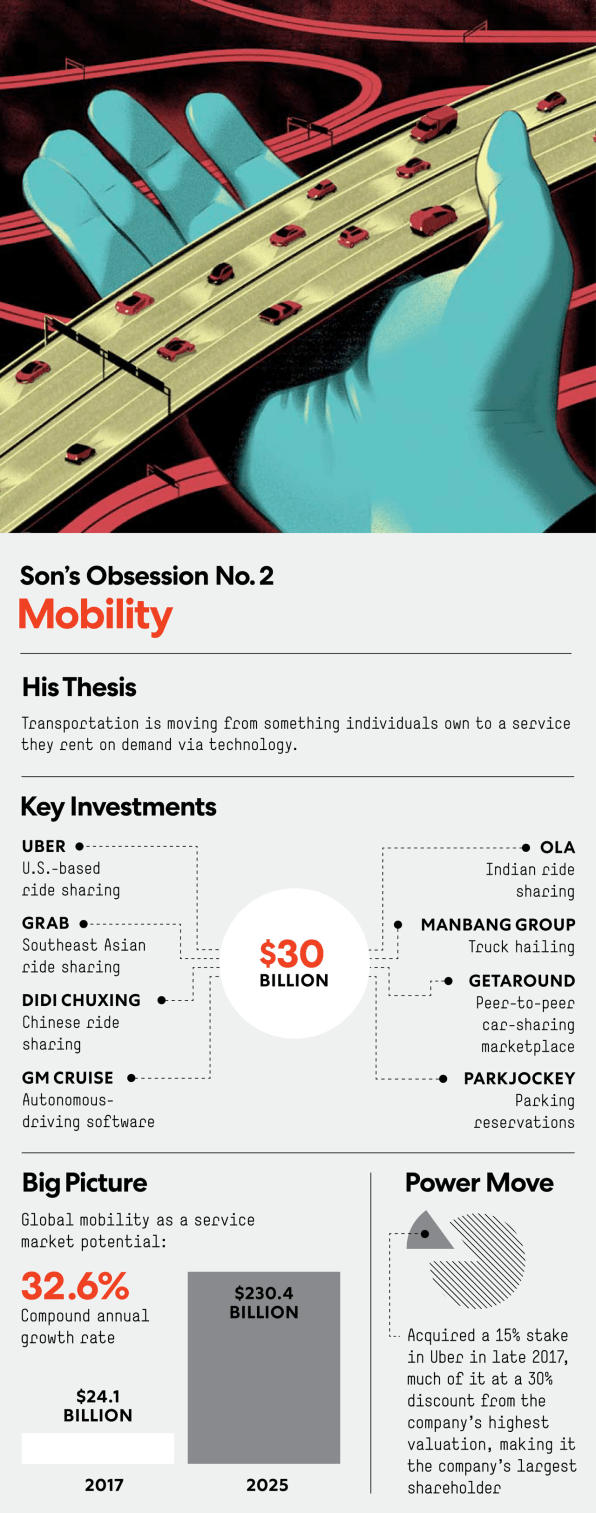

Son is not focused on profit margins during these meetings. What he wants to know is, How fast can the company go? This has a hypnotic effect on his portfolio CEOs. “Masa told me, ‘The entrepreneur’s ambition is the only cap to the company’s potential,’ ” recalls Robert Reffkin, cofounder and CEO of the real estate brokerage platform Compass (who says Son also asked him the question about what he would do if money were no object). Sam Zaid, CEO of the car-sharing platform Getaround, remembers Son inquiring, “How can we help you get 100 times bigger?” before ultimately giving him $300 million in August 2018. Even proven winners are not impervious to Son’s motivational gifts. “It is people like Masa who can accelerate our world,” says Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi, who counts Son as his biggest investor. Khosrowshahi says Son’s backing will be key to helping him build Uber into “the Amazon of transportation.” And when Housenbold first met Son, the SoftBank chairman told his future Vision Fund partner, “We are going to change the world.”

Dave Grannan, cofounder and CEO of Light, another startup building 3-D cameras to be the eyes of self-driving vehicles, met the SoftBank leader in Tokyo last spring. (Son’s strategy is to make multiple bets in the same categories; the house wins either way.) Grannan was in Son’s office presenting how his technology works when Son grabbed a camera that the founder had brought with him as part of the demonstration. Son aimed its lens at a picture hanging on the wall, a portrait of a man who looked like a Japanese samurai from long ago. He then handed the camera back to Grannan without explanation. Later, Grannan, feeling that it might be significant, looked up the image. The subject was Sakamoto Ryoma, a famous ronin adventurer who rose from humble beginnings to overthrow the feudal shoguns of the Tokogawa era and launch Japan into the modern age. He is Son’s childhood hero. “Every morning when I come to work, it reminds me to make a decision worthy of Ryoma,” Son once told an audience. “Ryoma was the starting point in my life.”

Son grew up poor on the remote island of Kyushu, in southern Japan. His family had emigrated from Korea in the 1960s at a time when racism and anti-foreign sentiment were rampant. His parents had named him Masayoshi, the Japanese word for “justice,” because they hoped an honorable-sounding name would deflect cultural prejudices that cast Koreans as crooks, liars, and thieves. It didn’t work: Son was bullied at school.

Son drew strength from his relationship with his father, who was convinced that his child was destined for greatness. Once, while in elementary school, Son told his father, Mitsunori, that he wanted to be a teacher. Mitsunori, now 82, told him he was thinking too small about his future: “I believe you are a genius,” he said, according to Japanese biographer Atsuo Inoue in his 2004 book, Aiming High. “You just don’t know your destiny yet.” When Mitsunori was struggling to start a coffee shop, he asked his son to help him find customers. Son told him to offer free coffee to lure them in–and make up the losses once they came through the door. Mitsunori handed out drink vouchers on the street, and soon the café was full.

After earning a degree from UC Berkeley in economics and computer science, Son returned to Japan and launched SoftBank in 1981. He had only two part-time employees and no customers, but he had mapped out a 50-year plan for the company that started with selling computer software. It didn’t matter that, back then, very few people had computers and there was virtually no software business. When he told his two employees, “In five years, I’m going to have $75 million in sales,” the pair promptly quit.

To drum up business, he even followed the same advice he once gave his father: He handed out free modems on the street. Another time, Son reserved the largest booth at an electronics trade show and spent everything he had on fliers, displays, and a sign that read now the revolution has come. His booth drew a crowd, but still no sales. But he persevered, and by the mid-1990s, SoftBank was the largest software distributor in Japan and Son took the company public on the Japanese stock market.

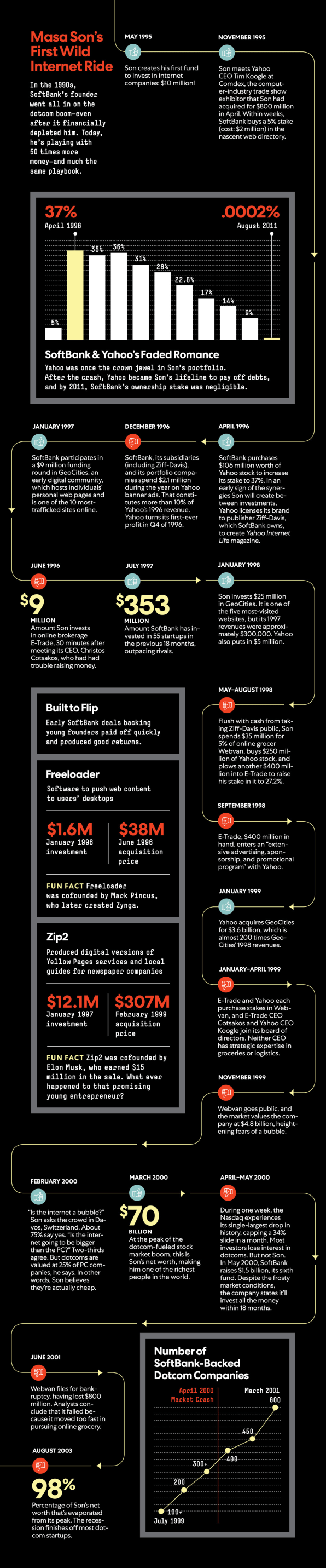

Son was drawn to the burgeoning internet boom of that era, and his attention turned to the United States. Success with investments in Yahoo and E-Trade led the company to make others, and by 1997, Silicon Valley’s local newspaper labeled SoftBank the most active internet investor. “Our über-strategy is to get everyone’s eyeballs, then their money, then a piece of everything they do,” one of the company’s VCs later told Forbes. In January 2000, two months before the peak of the dotcom era, Son claimed to own more than 7% of the publicly listed value of the world’s internet companies, via more than 100 investments. As Son has told the story, at one point his personal net worth was rising by $10 billion per week; for three days, he was richer than Bill Gates. But SoftBank’s stock slid as investors started to question Son’s relentless dealmaking, particularly his decisions to acquire a bank and bring the Nasdaq stock market to Japan via a joint venture. Rivals and skeptics believed these moves would be used, respectively, to fund SoftBank investments and take them public. Then the U.S. markets crashed, in April 2000, and the stocks of such SoftBank high-fliers as Buy.com, Webvan, and even Yahoo collapsed. Son, a true believer, only sped up his investing in the face of the dotcom apocalypse. By March 2001, The Wall Street Journal reported that SoftBank had bet on 600 internet companies. By that count, he’d more than tripled his exposure in 14 months. During that same time, SoftBank’s stock fell 90%, and $70 billion of Son’s net worth disappeared.

“Most human beings who’ve had the kinds of experiences he’s had become tentative,” says Michael Ronen, who has worked with Son for 20 years, first as a banker at Goldman Sachs and now as a partner in the Vision Fund. But Son, friends say, thrives on the edge. “You’ve never seen someone so fearless,” says Ronen.

Even as Son’s empire was tanking, he invested $20 million for a 34% stake in a then obscure Chinese e-commerce site run by a former teacher. Fourteen years later, when that company, Alibaba, went public, that stake was worth $50 billion.

“Twenty years ago, the internet started, and now AI is about to start on a full scale,” Son told investors and analysts this past November while reporting SoftBank’s second-quarter results. Standing on stage in Tokyo, he laid out the numbers to back up his assertion. Behind him, a slide featured dozens of companies in the Vision Fund’s portfolio, many now valued at more than $1 billion (in part due to SoftBank’s largesse). The Vision Fund’s returns–after selling its stake in Indian e-commerce company Flipkart to Walmart in May 2018–had boosted SoftBank’s operating profits by 62%.

Son and his colleagues refer to his strategy by using the Japanese phrase gun-senryaku, which can mean a flock of birds flying in formation. (Son also refers to his investments as his cluster of number ones.) Collectively, these enterprises are moving faster–and more forcefully–than they ever could individually. Those on the inside say it is even more rapid than anyone on the outside realizes. Over the summer, Son asked Claure, his COO, to start a new internal division devoted to “value creation.” Its purpose is to help Vision Fund entrepreneurs access SoftBank’s vast global resources and partnerships. Claure currently has 100 people working on the team, technically known as the SoftBank Operating Group, and expects to have 250 dedicated to these efforts by sometime next year.

A key element of this value creation comes from connecting companies to help each other grow. Son hosts dinners and events to bring people together, and he suggests they use each other’s services (a strategy he also deployed in the 1990s). For example, Compass and Uber rent space from WeWork. Mapbox, an AI-powered navigation system, inked a deal with Uber last fall. Nauto has met with executives from GM Cruise, the self-driving software maker in which SoftBank invested $2.25 billion last spring. Son’s introductions help entrepreneurs feel more connected to a bigger purpose. “The family concept really does work,” says Nauto CEO Stefan Heck. “There is a level of trust among us that we are all building toward this vision.”

One evening last fall, Son hosted a dinner at his home for his senior investing team. Gathered around Son’s dining table, the group discussed the company’s future. Son mentioned some companies he’d recently met with in Asia that were finding new ways to apply artificial intelligence to their businesses. He explained why he believed AI could cross into so many different industries, which spurred a lively conversation about the new opportunities others at the table were seeing. There was a sense of enormous forward momentum. Where else could they go?

Sometimes, though, the universe presents an unexpected detour. Right around the time of the dinner, news broke that operatives working directly for SoftBank’s biggest investor, the Saudi Arabian government, had murdered Saudi journalist (and American resident) Jamal Khashoggi. Almost immediately, Son was thrown into a geopolitical maelstrom. SoftBank’s stock plummeted as investors fretted about the implications of his close ties to Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, whom the CIA concluded had personally issued the kill order. Only a month earlier, after committing $45 billion to back a second fund, bin Salman told Bloomberg that without Saudi backing, “there will be no Vision Fund.”

As gruesome details about the murder emerged, the pressure on Son became intense. “Right now, any CEO taking money from SoftBank would put him or herself at risk of an employee revolt,” one top Silicon Valley investor told me a week after the murder. “No one wants to be connected with blood money.” Some of Son’s Vision Fund companies publicly tried to distance themselves from Saudi Arabia (Compass’s Reffkin issued a statement saying, “The death of Jamal Khashoggi is beyond disturbing because the freedom and safety of the press is something that is incredibly important to me.”) Uber’s Khosrowshahi and Arm’s Segars pulled out of a major Saudi investment conference in Riyadh in October. Son did as well, but another Vision Fund partner did participate—and Son met privately with bin Salman that week in Riyadh. What they discussed has not been disclosed, but it is clear that somehow Son was reassured. In November, he announced plans for a $1.2 billion solar grid outside of the Saudi capital. “As horrible as this event was, we cannot turn our backs on the Saudi people as we work to help them in their continued efforts to reform and modernize their society,” Son said in a statement. “MBS seems to be riding out the controversy,” says Karen E. Young, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, pointing out that for anyone interested in doing business in the Middle East, Saudi Arabia cannot be ignored. “[Son] is a businessman. He is not going to turn his back on $45 billion.”

The global network that Son has built during his four-decade career is as vast–and important to him–as his war chest, friends say. It includes business leaders such as Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, and Jack Ma, and world leaders such as China’s Xi Jinping, India’s Nahendra Modi, and Donald Trump. “You have to remember who helped you along the way and the loyalty that one has to show for your partners during good times and bad times,” says one person close to Son.

Son is working to ensure that the Vision Fund can survive, with or without Saudi money: SoftBank secured some $13 billion in loans from banks last fall, including Goldman Sachs, Mizuho Financial, Sumitomo Mitsui Financial, and Deutsche Bank. Son has also made clear that the Vision Fund is very much open for business, announcing a slew of new deals, including $1.1 billion for View (a maker of “smart” windows), $375 million for Zume (which builds robots that can cook), and that lead investment in ByteDance and its AI-powered news and video apps. “This is just the beginning,” Rajeev Misra tells me in December. Over the next year, the Vision Fund plans to back dozens of new AI-driven startups, almost doubling its portfolio from 70 to 125 companies.

There is no one on the planet right now in a better position to influence this next wave of technology as Son. Not Jeff Bezos, not Mark Zuckerberg, not Elon Musk. They might have the money but not Son’s combination of ambition, imagination, and nerve. The network of companies within the Vision Fund, if they succeed, will reshape critical pieces of the economy: the $228 trillion real estate market, the $5.9 trillion global transportation market, the $25 trillion retail business. We won’t be able to turn Vision Fund–backed services and technologies off like computers and smartphones. They will, ultimately, have minds and thoughts of their own.

Of course, Son is not an unstoppable force. Any number of factors–economic downturns, geopolitical crises, government regulators–could upend his best-laid plans. There’s always the possibility he could be betting on the wrong companies. Son, however, doesn’t have time to traffic in doubt. “There are good times and bad times,” he proclaimed when he launched the Vision Fund, “but SoftBank is always there.”